Okay, who armed the parakeets…?

Young Mahito (Soma Santoki) awakens in the night to a commotion, following his panicked father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) into the streets toward a hospital in Tokyo where his mother works… moments before it collapses in flames. Two years later, Shoichi moves out of the city to work toward the war effort, introducing Mahito to his new stepmother Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) — also his mother’s sister and also very pregnant. The boy projects stoicism but harbors anger in his heart, exacerbated by a gray heron (Masaki Suda) that taunts and inexplicably speaks to him. With the discovery of an overgrown crumbling tower hidden on the property and a story about a great uncle who lost his mind “by reading too many books,” it isn’t until Natsuko goes missing that Mahito willingly enters the forbidden tower. Accompanied by Kiriko (Kou Shibasaki), one of the six grannies who work for Shoichi, the boy discovers a dreamlike world beyond his own where nothing and everything seems familiar.

Writer/director Hayao Miyazaki has been working in animation for decades, moving into the mainstream with Princess Mononoke in 1997. He founded Studio Ghibli in the mid 1980s, hiring animators from ailing studio Topcraft who’d recently completed outsourced work for Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn for Rankin/Bass. While The Wind Rises was seen as the final full-length work from the creator, the existence of The Boy and the Heron was a surprise to fans, dealing with themes of death, loss, and war from a child’s perspective… and perhaps the final film from the director. Reportedly semi-autobiographical, it’s taken as a deeply personal work, but will audiences who are not Hayao Miyazaki connect with it on the same level?

We can tell the boy is depressed because he gets into fights at school, and we can tell the stepmother is depressed because she stays in bed. This shorthand seems to be good enough for Miyazaki’s narrative but feels too subtle to be affecting, reducing Mahito to more of a spectator than a participant. When the boy does act, everything inexplicably works out, as if the act of taking action was all that was required, never with any worry or doubt. Is he wise beyond his years or intentionally underwritten? Even the lines drawn to depict the character seem simple, but it isn’t clear if it’s to show Mahito’s youth — the elder grannies all seem shorter than the boy with grotesque giant heads — or to show him as pretty and upper class like his stepmother and father. Only when the stepmother becomes distraught does her face gain any distention detail, but at least someone felt something. It’s clear events are happening, but when the main character is given little ability to emote, viewers are given little reason to care. Finally there’s the gray heron himself, or “the Heron Man” as he’s later referred; whereas Mahito is dull, the heron is merely annoying.

Two films immediately come to mind when exploring these themes. Bastian from The NeverEnding Story was dealing with the loss of his mother, school bullies who won’t leave him alone, and a father who expects him to stop daydreaming, all which push him into a fantasy world ; unlike Bastian, Mahito appears stoic, emulating his father’s wartime demeanor. In Pan’s Labyrinth, Ofelia’s stepfather is a warmonger himself, lording over her mother, pregnant with a little brother. Mahito and Ofilia both enter their fantasy worlds determined to save someone else, but where Ofelia’s burden can never be undone, Mahito remains unaffected and ultimately detached. In terms of animation, the static images of old homes and hidden towers are beautifully rendered, but the simplicity of the animation exacerbates the disconnection, like a serene landscape painting before noticing a stick bug crawling over it.

In a Raiders of the Lost Ark kind of way, Mahito’s mere presence is somehow a catalyst, “the long-awaited one” to hasten what was always going to happen anyway, but Indiana Jones is interesting enough as a character to make up for it. Just imagine the 1986 film Labyrinth if the child was taken without goblyn king Jareth being invoked, and Sarah recovering the child free of temptation and never being fooled once; pretty dull, right? While the metaphors are ever-present, this narrative has all the excitement of a self-guided tour to an American roadside attraction.

The Boy and the Heron is rated PG-13 for some violent content, bloody images, smoking, and why do the Warawara look like Adipose from “Doctor Who?”

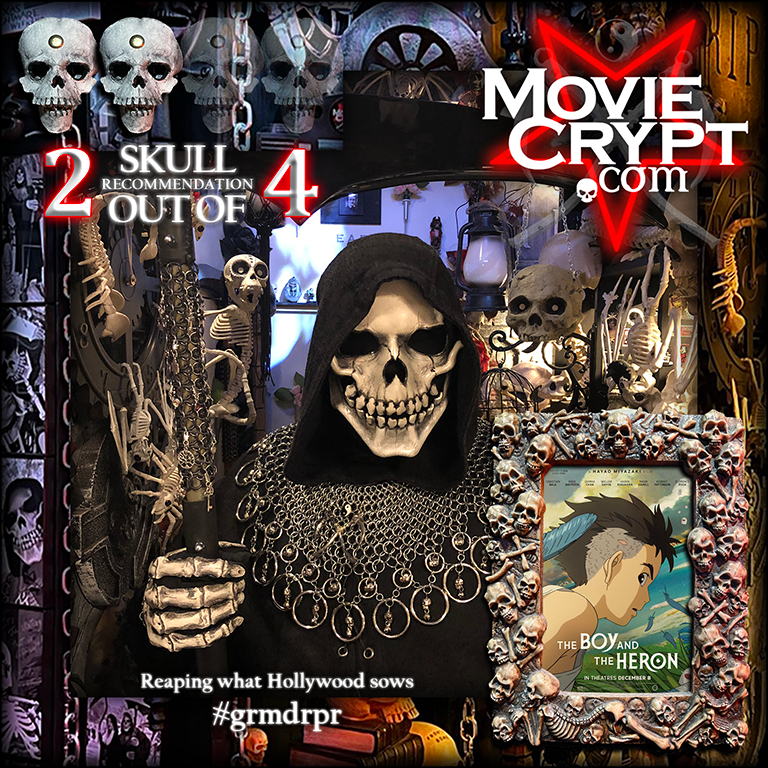

Two skull recommendation out of four

you are the dumbest person in the world

LikeLiked by 1 person

How could I ever argue with “Tony baloney?” The mind boggles. 💀

LikeLike